The Greek stauros is translated throughout our Bibles as ‘cross.’ The Watchtower ‘cross’ is a stake, an upright post, and the Watchtower’s New World Translation translates stauros according to its strict dictionary definition, torture stake. A Jehovah’s Witness will earnestly impress upon you the importance of getting this Greek word translated correctly, and will tell you about the questionable pagan origins of the symbol of the cross. It is worth asking, of course, How reliable is the NWT?.

This article builds on and expands two recent blog posts. Here we look in greater detail at the Watchtower ‘cross.’

The Watchtower Cross

In their Insight on the Scriptures the Watchtower Society writes:

‘TORTURE STAKE. An instrument such as that on which Jesus Christ met death by impalement. (Mt.27:32-40; Mr 15:21-30; Lu 23:26; Joh 19:17-19, 25) In classical Greek the word (stau·ros#) rendered “torture stake” in the New World Translation primarily denotes an upright stake, or pole, and there is no evidence that the writers of the Christian Greek Scriptures used it to designate a stake with a crossbeam.—See IMPALEMENT; Int, pp. 1149-1151. The book The Non-Christian Cross, by John Denham Parsons, states: “There is not a single sentence in any of the numerous writings forming the New Testament, which, in the original Greek, bears even indirect evidence to the effect that the stauros used in the case of Jesus was other than an ordinary stauros; much less to the effect that it consisted, not of one piece of timber, but of two pieces nailed together in the form of a cross…it is not a little misleading upon the part of our teachers to translate the word stauros as ‘cross’ when rendering the Greek documents of the Church into our native tongue, and to support that action by putting ‘cross’ in our lexicons as the meaning of stauros without carefully explaining that that was at any rate not the primary meaning of the word in the days of the Apostles, did not become its primary signification till long afterwards, and became so then, if at all, only because, despite the absence of corroborative evidence, it was for some reason or other assumed that the particular stauros upon which Jesus was executed had that particular shape.” —London, 1896, pp. 23, 24.

In my first blog post on the subject I showed how typically questionable is this authority, John Denham Parsons, they so enthusiastically quote. Read the post yourself and see how, among other things, he was into psychic phenomena (I imagine that rings a bell for some).

Bullingerism

On their website there is another example of questionable sourcing which we will look at briefly here. They write:

‘Many view the cross as the most common symbol of Christianity. However, the Bible does not describe the instrument of Jesus’ death, so no one can know its shape with absolute certainty. Still, the Bible provides evidence that Jesus died, not on a cross, but on an upright stake.

‘The Bible generally uses the Greek word stau·rosʹ when referring to the instrument of Jesus’ execution. (Matthew 27:40; John 19:17) Although translations often render this word “cross,” many scholars agree that its basic meaning is actually “upright stake.” According to A Critical Lexicon and Concordance to the English and Greek New Testament, stau·rosʹ“never means two pieces of wood joining each other at any angle.”

‘The Bible also uses the Greek word xyʹlon as a synonym for stau·rosʹ. (Acts 5:30; 1 Peter 2:24) This: word means “wood,” “timber,” “stake,” or “tree.” The Companion Bible thus concludes: “There is nothing in the Greek of the N[ew] T[estament] even to imply two pieces of timber.”’

As with John Denham Parsons, I asked myself who is the author of this Critical Lexicon and Concordance to the English and Greek New Testament? It is a 19th century Anglican cleric by the name of E W Bullinger. This venerable gentleman was a prodigious writer who believed the gospel is written in the stars, the constellations being pre-Christian expressions of Christian doctrine.

He believed enthusiastically in biblical numerology, taught soul sleep, was a hyper-dispensationalist (sometimes called Bullingerism), and a flat earther.

He also believed The Five Crosses (right) erected at Ploubezre, near Lannion, Côtes-du-Nord, in Brittany, France proved his theory that Christ was crucified with not two but four thieves. Note in the photograph the crossbeams.

As to the Companion Bible so readily cited for the translation of xylon, the primary editor of this volume was – E.W. Bullinger. I get the impression the Watchtower doesn’t travel any further than they have to in order to find an ‘authority’ to endorse their preconceived views. Unfortunately, most people don’t know the right questions to ask and are left impressed by what only appears to be sound scholarship; so it’s up to us.

‘In your hearts honour Christ the Lord as holy, always being prepared to make a defence to anyone who asks you for a reason for the hope that is in you; yet do it with gentleness and respect…’

(1 Pet.3:15)

Stauros

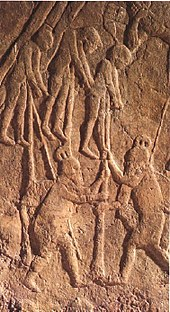

Strictly speaking, of course, stauros means a stake. This pre-existing, unremarkable item was adopted very early by Assyrians, Phoenicians, and Babylonians for use in torture and execution. Initially the stauros was used to impale people, as in this relief showing Judeans being impaled by the Assyrian military under Sennacherib.

The Assyrians often would impale victims in great numbers alive on stauros outside a fortified city they sought to conquer. It was a means of psychological warfare. The victims’ screams were expected to convince the city’s inhabitants that it would be better to surrender and avoid the same fate.

Victims were also nailed to stakes, hands and feet, prolonging their suffering by giving them anchors against which to push to temporarily relieve their suffocation and extend their agonies. This method of torture and execution was adopted by Alexander the Great in his siege and conquest of Tyre. The victim might also be nailed to the trunk of a tree, arms extended on branches.

The Christian Cross

The Romans, in the first century BC, adopted this means of torture and execution, their victims coming from the lowest strata of society. The New Bible Dictionary explains, ‘Only slaves, provincials, and the lowest types of criminals were crucified, rarely Roman citizens,’ (The latter for high treason). This explains why tradition has Peter being crucified upside down while Paul, a Roman citizen, was beheaded. So, did Peter die on the Watchtower ‘cross’, or on the Christian Cross? More to the point, how did did Jesus die? He certainly did die on a stauros, but not on the Watchtower ‘cross’.

Archaeology

In 1968 in an ossuary from burial caves at Giv’at ha-Mivtar in Jerusalem were found the remains of a man, aged 24-28, who had been crucified and died about the year A.D. 70. This was the first time that archaeologists had discovered actual physical remains of a victim, even though thousands had been executed this way. Of course, if the great majority were the lowest in society, it is hardly surprising their remains would not be found.

The bones in the ossuary showed the man’s legs had been broken deliberately after the arms and legs had been nailed to a cross of olive wood. The single nail that had pierced the feet had penetrated the ankle bones and could not be extracted before burial. N. Haas of the Department of Anatomy at Hebrew University described the find in an article published in the Israel Exploration Journal in 1970:

‘The whole of our interpretation concerning the position of the body on the cross may be described briefly as follows: The feet were joined almost parallel, both transfixed by the same nail at the heels, with the legs adjacent; the knees were doubled, the right one overlapping the left; the trunk was contorted; the upper limbs were stretched out, each stabbed by a nail in the forearm.’ (emphasis added)

The Romans would have used stakes of course but the evidence shows they also used a cross. It was the Romans who introduced the cross beam, making the stake a cross. The crossbeam has a Latin name, furca or patibulum, and slaves were made to carry this patibulum to the place of execution. Furca is an interesting word. It refers to a forked like structure, a central pole or stake from which there were protrusions. It is from this we get our English fork.

The typical crucifixion is described in the Jewish Encyclopaedia:

‘The crosses used were of different shapes. Some were in the form of a ![]() , others in that of a St. Andrew’s cross,

, others in that of a St. Andrew’s cross, ![]() , while others again were in four parts,

, while others again were in four parts, ![]() . The more common kind consisted of a stake (“palus”) firmly embedded in the ground (“crucem figere”) before the condemned arrived at the place of execution (Cicero, “Verr.” v. 12; Josephus, “B. J.” vii. 6, § 4) and a cross-beam (“patibulum”), bearing the “titulus”—the inscription naming the crime (Matt. xxvii. 37; Luke xxiii. 38; Suetonius, “Cal.” 38). It was this cross-beam, not the heavy stake, which the condemned was compelled to carry to the scene of execution (Plutarch, “De Sera Num. Vind.” 9; Matt. ib.; John xix. 17; The cross was not very high, and the sentenced man could without difficulty be drawn up with ropes (“in crucem tollere, agere, dare, ferre”). His hands and feet were fastened with nails to the cross-beam and stake (Tertullian, “Adv. Judæos,” 10; Seneca, “Vita Beata,” 19); though it has been held that, as in Egypt, the hands and feet were merely bound with ropes (see Winer, “B. R.” i. 678). The execution was always preceded by flagellation (Livy, xxxiv. 26; Josephus, “B. J.” ii. 14, § 9; v. 11, § 1); and on his way to his doom, led through the most populous streets, the delinquent was exposed to insult and injury. Upon arrival at the stake, his clothes were removed, and the execution took place. Death was probably caused by starvation or exhaustion, the cramped position of the body causing fearful tortures, and ultimately gradual paralysis. Whether a foot-rest was provided is open to doubt; but usually the body was placed astride a board (“sedile”). The agony lasted at least twelve hours, in some cases as long as three days. To hasten death the legs were broken, and this was considered an act of clemency (Cicero, “Phil.” xiii. 27). The body remained on the cross, food for birds of prey until it rotted, or was cast before wild beasts. Special permission to remove the body was occasionally granted. Officers (carnifex and triumviri) and soldiers were in charge.’

. The more common kind consisted of a stake (“palus”) firmly embedded in the ground (“crucem figere”) before the condemned arrived at the place of execution (Cicero, “Verr.” v. 12; Josephus, “B. J.” vii. 6, § 4) and a cross-beam (“patibulum”), bearing the “titulus”—the inscription naming the crime (Matt. xxvii. 37; Luke xxiii. 38; Suetonius, “Cal.” 38). It was this cross-beam, not the heavy stake, which the condemned was compelled to carry to the scene of execution (Plutarch, “De Sera Num. Vind.” 9; Matt. ib.; John xix. 17; The cross was not very high, and the sentenced man could without difficulty be drawn up with ropes (“in crucem tollere, agere, dare, ferre”). His hands and feet were fastened with nails to the cross-beam and stake (Tertullian, “Adv. Judæos,” 10; Seneca, “Vita Beata,” 19); though it has been held that, as in Egypt, the hands and feet were merely bound with ropes (see Winer, “B. R.” i. 678). The execution was always preceded by flagellation (Livy, xxxiv. 26; Josephus, “B. J.” ii. 14, § 9; v. 11, § 1); and on his way to his doom, led through the most populous streets, the delinquent was exposed to insult and injury. Upon arrival at the stake, his clothes were removed, and the execution took place. Death was probably caused by starvation or exhaustion, the cramped position of the body causing fearful tortures, and ultimately gradual paralysis. Whether a foot-rest was provided is open to doubt; but usually the body was placed astride a board (“sedile”). The agony lasted at least twelve hours, in some cases as long as three days. To hasten death the legs were broken, and this was considered an act of clemency (Cicero, “Phil.” xiii. 27). The body remained on the cross, food for birds of prey until it rotted, or was cast before wild beasts. Special permission to remove the body was occasionally granted. Officers (carnifex and triumviri) and soldiers were in charge.’

I have referred throughout to the ‘Watchtower cross’ deliberately to make a point. The meanings of words have been known to change with time and usage. While stauros denotes an upright stake in ancient times, by Roman times it also referred to a cross, or to the crossbeam carried by the condemned man. Usage has given stauros a second meaning and the ‘Watchtower stake’ becomes the ‘Watchtower cross.’ Strong’s wisely distinguishes between definition (an upright stake) and usage (a cross) saying:

4716 staurós – the crosspiece of a Roman cross; the cross-beam (Latin, patibulum) placed at the top of the vertical member to form a capital “T.” “This transverse beam was the one carried by the criminal” (Souter).

Christ was crucified on a literal Roman cross (staurós). Staurós (“cross”) is also used figuratively for the cross (sacrifice) each believer bears to be a true follower-of-Christ (Mt 10:38, 16:24, etc.). The cross represents unspeakable pain, humiliation and suffering – and ironically is also the symbol of infinite love! At the cross, Jesus won our salvation – which is free but certainly not cheap! For more discussion on the untold suffering of Christ on the cross see stauróō (“to crucify on a cross”).

[The “cross” (Mk 8:34) is not a symbol for suffering in general. Rather it refers to withstanding persecution (difficult times), by the Lord’s power, as He directs the circumstances of life. As Christ’s disciples, believers are to hold true – even when attacked by the ungodly.]

The Cross in the Bible

The New Bible Dictionary describes crucifixion in this way:

‘After a criminal’s condemnation, it was the custom for a victim to be scourged with a flagellum…He was then made to carry the cross-beam (patibulum) like a slave to the scene of his torture and death, always outside the city, while a herald carried in front of him the ‘title’, the written accusation. It was this patibulum, not the whole cross, which Jesus was too weak to carry, and which was borne by Simon the Cyrenian. The condemned man was stripped naked, laid on the ground with the cross-beam under his shoulders and his arms or his hands tied or nailed (Jn.20:25) to it. This cross-bar was then lifted and secured to the upright post, so that the victim’s feet, which were then tied or nailed, were just clear of the ground, not high up as so often depicted. The main weight of the body was usually borne by a projecting peg (sedile), astride which the victim sat. There the condemned man was left to die of hunger and exhaustion. Death was sometimes hastened by the crurifragum, breaking of the legs, as in the case of the two thieves, but not done in our Lord’s case, because he was already dead.’

Flagellum, patibulum, sedile, crurifragum, all Latin words describing the common Roman instruments of torture, all absent from the Watchtower depiction of crucifixion. They stick studiously, assiduously, to the Greek in order to drive home their point that stauros means ‘stake.’ Yet, those Latin words exist in the language of Rome because the instruments they describe exist in the history of Roman crucifixion.

The Watchtower object that the gospel writers did not use patibulum but stauros, as did the later New Testament writers. The problem with this is Jesus and his followers spoke Aramaic, Hebrew, especially in reading the Scriptures (Lk.4:16), and the common language of the empire was Greek, the language in which the New Testament was written. Latin was used for legal and military matters. See What Language did Jesus Speak? It would not have occurred to them to reach for a Latin word. They were telling their story in the language and idiom most familiar to them and their world.

As I pointed out above, Strong’s wisely distinguishes between definition (an upright stake) and usage (a cross) which, simply put, means stauros became the common word in the Greek speaking world for the Latin cross, or any part of the cross, including the patibulum. That is how language works.

In the quote above from their own website they recognise this, ‘The Bible also uses the Greek word xyʹlon as a synonym for stau·rosʹ. Pick up a dictionary, look up the word ‘square’ and see for yourself how many different meanings a single word can have. In my dictionary open in front of me I find 14 meanings in the main entry.

The New International Dictionary of New Testament Theology states:

‘Two words are used for the instrument of execution on which Jesus died: xylon (wood, tree) and stauros (stake, cross). xylon meant originally wood, and is often used in the NT of wood as a material. Through its connection with Duet.21:23 (quoted in Gal.3:13, ‘Cursed be everyone who hangs on a tree.’) xylon could virtually be treated as synonymous with stauros.’

The dictionary goes on to identify the different uses of xylon (originally meaning wood) It lists: wood or timber for building material, fuel, utensils and cultic objects, clubs. Instruments of torture and punishment in the form of sticks, blocks and collars for slaves, lunatics, and prisoners were all called xylon.

As in an instrument of torture and execution, ‘stauros can mean a stake which was sometimes pointed on which an executed criminal was publicly displayed n shame as a further punishment, It could be used for hanging, impaling, strangulation. stauros could also be an instrument of torture, perhaps in the sense of the Lat. patibulum, a cross-beam laid on the shoulders. Finally it can be an instrument of execution in the form of a vertical stake and a cross-beam of the same length forming a cross in the narrower sense of the term.’

So, xylon (orig. wood) has a variety of applications and, ‘could virtually be treated as synonymous with stauros.’ stauros (orig. stake) has a variety of applications but, ‘could also be an instrument of torture, perhaps in the sense of the Lat. Patibulum, a cross-beam laid on the shoulders.’

The gospel accounts harmonise perfectly with the accounts of crucifixion above. Matthew records:

‘Then he released Barabbas, and having scourged Jesus, delivered him to be crucified…And when they had mocked him, they stripped him of the robe and put his own clothes on him and led him away to crucify him. As they went out, they found a man of Cyrene, Simon by name. They compelled this man to carry his cross. And when they came to a place called Golgotha (which means Place of the Skull), they offered him wine to drink, mixed with gall, but when he tasted it, he would not drink it. And when they had crucified him, they divided his garments among them by casting lots. Then they sat down and kept watch over him there. And over his head they put the charge against him, which read, ‘This is Jesus, the King of the Jews.’ (Mt.27:26,31-37; Mk.15:14-26; Lk.23:26-38; Jn.19:1-22)

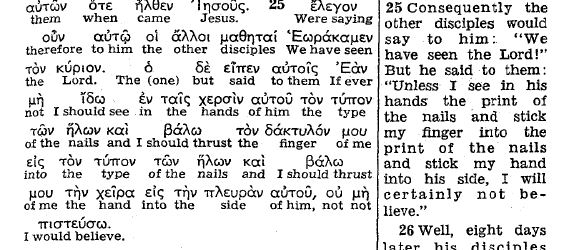

In John’s gospel we encounter the understandable scepticism of Thomas who, when, ‘the other disciples told him, ‘We have seen the Lord.’ [Thomas] said to them, ‘Unless I see in his hands the mark of the nails, and place my finger into the mark of the nails, and place my hand into his sider, I will never believe.’ (Jn.20:24-25) Note the plural nails, indicating Thomas knew full well how his Lord had died, with a nail in each hand.

The Watchtower Cross: A Curious Irony

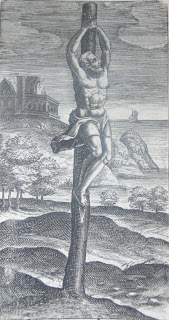

In the 1950 and 1969 editions of their New World Translation there was a note and illustration reinforcing the case for a stake. Having been exposed as being less than truthful about their claim they have omitted it from later editions. However, at the back of my 1985 edition of the Kingdom Interlinear Translation of the Greek Scriptures it still says:

‘A single stake for impalement of a criminal was called in Latin crux sim’plex. One such instrument of torture is illustrated by Justus Lipsius (1547-1606) in his book De cruce libre tres, Antwerp, 1629, p. 19, which we here present.’ (KIT, 1985, p.1150)

Imagine sitting in the Kingdom Hall on a Thursday evening, a new and enthusiastic Witness perhaps, and being taught this. Imagine being taught and shown this in your home by a couple of Jehovah’s Witnesses and being impressed with the academic precision of this teaching. They seem to handle this material with such authority and confidence. You have nothing with which to compare it and why should you try, the evidence seems overwhelming.

The problem with this citation is Justus Lipsius’ book simply states this was one method of crucifixion. I have found an excellent blog post by Stephen E Jones looking in depth at the error of the Watchtower Society in this matter. You can see here why they removed the claim from subsequent editions of the NWT but one wonders why they continued to use it in their KIT.

There is no mention of Justus Lipsius on their website. One wonders why, if they have realised their error, they haven’t simply changed their teaching. They won’t be the first in history and there is no shame and much kudos in admitting your error. Don’t they talk about ‘new light?’

The evidence for the Christian Cross is overwhelming and there are three solid facts we can take away with us to use in our next doorstep encounter with Jehovah’s Witnesses.

1. Reliable accounts of crucifixion, along with archaeological evidence, demonstrate that the Romans used different methods of crucifixion, including both stakes and crosses. The Watchtower Society presents its evidence in classical Greek, while the New Testament was written in common, or Koine, Greek. In the language of the streets definitions are even more fluid that in a dictionary, and a distinction is reasonably made between the literal translation of stauros, and the meaning in popular usage.

The Romans had their own legal and military language to describe this most cruel of tortures. Their word for the crossbeam that Jehovah’s Witnesses insist was not used in Christ’s execution is patibulum. If there was no cross then what did the Romans mean when speaking of the patibulum? Perhaps when a Jehovah’s Witness raises the strict definition of the Greek stauros it would be useful to ask if they know the role of the Latin patibulum in Roman crucifixion. Why didn’t the gospel writers and later disciples use the word patibulum? Because Greek was the common language not Latin, and stauros had passed into the vocabulary to indicate more than a stake.

2. It is an established historical fact that the condemned man was made to carry the patibulum (not the stake) to his place of execution before being nailed to it and lifted up onto the static stake. Jesus urged his followers to carry their own cross (stauros):

‘Then Jesus told his disciples.’If anyone would come after me, let him deny himself and take up his cross and follow me. For whoever would save his life will lose it, but whoever loses his life for my sake will find it.’ (Mt.16:24-25)

This is a striking image and would have readily been understood by his disciples as mirroring in some way the dreadful but common sight of the condemned carrying the cross-beam as a punishment. It doesn’t mean carrying a burden, a ‘cross I have to bear,’ as is popularly believed. Rather, it means being prepared, in the face of the world’s mockery, to suffer the humiliation (in the world’s eyes) of dying to self and living for Christ.

3. We have Thomas’ words, ‘Unless I see in his hands the mark of the nails, and place my finger into the mark of the nails, and place my hand into his side, I willnever believe.’ (Jn.20:24-25) indicating Thomas knew more than one nail was driven into Jesus’ hands.

The most important thing about the crucifixion, of course, is what was achieved at Calvary where:

‘He was wounded for our transgressions;

He was crushed for our iniquities;

upon him was the chastisement that brought us peace,

and with his stripes we are healed.’ (Is.53:5)

‘Therefore, since we have been justified by faith, we have peace with God through our Lord Jesus Christ. Through him we have also obtained access by fatih into his grace in which we stand, and we rejoice in hope of the glory of God.’ (Ro.5:1-2)

This is the message that turned the world upside down. This is the hope that still upends this world as each one comes to him, each heart is changed, and new life is given. All because of the Cross of Christ.