An unofficial version list was compiled of 185 translations giving John 1:1 more or less as does the New World Translation. John 1:1 is a Jehovah’s Witness preoccupation, one of many as I’m sure you know. They typically appeal to numerous, usually obscure, often Unitarian versions of the New Testament to question the Trinity. Now, this is a legitimate enough pursuit if you are, as they are, Unitarian in your beliefs. However, if in this pursuit you use less than reliable sources to make your point then you can expect others to, just as reasonably, challenge you.

The Version List

The version list is a PDF document and currently available online. 185 seems an impressive number until you realise these examples date from the 15th century onward and from across the Christian and non-Christian world.

It is also worth noting that, as of October 2019 the full Bible has been translated into 698 languages, the New Testament has been translated into an additional 1,548 languages and Bible portions or stories into 1,138 other languages. Thus at least some portions of the Bible have been translated into 3,384 languages. According to one source there are 2083 versions of the Bible across the world.

The Magical Message of John

One example will suffice to explain why I wrote above, ‘non-Christianworld.’ The version list contains a reference to, The Magical Message according to Iôannes (To kata Ioannon Euangelion); by James M Pryse, commonly called the Gospel according to [St.] John New York: The Theosophical Publishing Company of New York. Pryse’s translation of the third clause of John 1:1 reads ‘and the Thought was a God.’ Who was James Pryse, and what is the Theosophical Society?

James Morgan Pryse (14 November 1859 – 22 April 1942) was an American author, publisher, and theosophist. He joined the Theosophical Society in July 1887. The Theosophical Society was founded by Madame Blavatsky and others in New York in 1875, and advocated a worldwide eclectic religion based largely on Brahmanic and Buddhist teachings.

It is a hermetic order holding that there is a deeper spiritual reality and that direct contact with that reality can be established through intuition, meditation, revelation, or some other state transcending normal human consciousness. John Pryse eventually left the Theosophical Society and, in 1928, founded the Gnostic Society in his Los Angeles home.

His theosophical and gnostic philosophy would have been incompatible with the Christian faith. This would have a significant bearing on his translation of a Christian text and this should be taken into account. His use of ‘Thought’ instead of, ‘Word’ for example, reflects his belief in spiritual progress by gnosis (knowledge) rather than by faith in Christ.

The Work of Translation

In Bible translation there is always going to be a degree of interpretation. The original Hebrew texts, for instance, have no vowels, and meaning can vary depending on which vowels are chosen. For all texts things we take for granted today, such as chapters, verses, punctuation, even simple spaces between words, are not found in original manuscripts.

Words don’t easily come across into a different language, grammar, syntax and meaning are different. There is scope for the translation philosophy of the translator to influence interpretation. Some translations are more literal, and less accessible to the typical reader, others are more accessible because more dynamic, but less literal, bringing across the thought of the text.

Archbishop Newcome

In this process, whether the translator favours a literal or a dynamic approach, there is a danger of prejudices and preconceptions influencing how the translation process proceeds. That is why the best translations are produced by a team of people and with editorial oversight. Another example from the version list illustrates this, demonstrating why we should be cautious about sources.

Consider, ‘The New Testament, in An Improved Version, Upon the Basis of Archbishop Newcome’s New Translation: With a Corrected Text, and Notes Critical and Explanatory.’ John 1:1 here gives us ‘and the Word was a god.’ Archbishop Newcome’s translation is very familiar, it is a staple source when the Watchtower Society wish to press their case.

The problem here is, while the ‘Improved Version, With a Corrected Text, and Notes Critical and Explanatory,’ does, indeed, give us ‘a god,’ this is not Archbishop Newcome’s rendering of the verse.

The simple explanation is, Archbishop Newcome was a Trinitarian, while Thomas Belsham ‘improved’ the text to suit his Unitarian convictions. It is disingenuous to point to Archbishop Newcome while quoting Thomas Belsham, when Newcome translated John 1:1, ‘…and the Word was God.’

William Tyndale

The argument being put is familiar enough. Since other translations translate the third clause of John 1:1 ‘and the word was god,’ or some form thereof, there is a strong case for the New World Translation. The version list includes many foreign language translations, about which I am not qualified to comment.

However, from the many English translations on the version list one JW apologist lifted the work of William Tyndale. It is this I want to address as a cautionary tale as he drew the following conclusions:

In defiance of the Catholic church, Tyndale set out to produce a bible (sic) for ordinary people, so that even a plough-boy could understand the word of God, eventually he was betrayed and murdered, but, before that occurred he managed to complete his bible (sic) translating work!

Below is an extract from his c. 1525 CE treatment of John 1:1

“In the begynnyng was that word and that worde was with god and god was that worde”

Here Tyndale uses the term “god” for both subjects, both in lower case letters and he used that same term “god” in the same chapter. As the years passed, we come to 1534, Tyndale revised the first use of God in John 1:1 in the second clause and used an uppercase “G”, so that we had “God”, not “god”, however, Catholic authorities were on his heels, he was caught in 1536 and murdered, but, not before he could complete his last revision of his work and it read:

“In the begynnyng was the worde and y worde was with God and the word was god.”

In his 1534 work Tyndale changed “god” for “God”, all except that is in the third clause of John 1:1, where he kept “the worde” as “god”, keeping the lowercase “g”, just before his arrest, in 1536, he produced his final revision and as can clearly be seen “god” in the third clause has a lower case ‘g.’

“In the begynnyng was the worde and y worde was with God and the word was god.”

Why is Tyndale on the Version List?

A couple of things might be observed. William Tyndale was a Trinitarian, and his work was partly funded by a Trinitarian group. One wonders why, then, Tyndale is on the list since he would disagree profoundly with the Watchtower position. It seems Tyndale is a towering authority for Jehovah’s Witnesses when it comes to his translation of this verse, but may be set aside as no authority at all when he inconveniently proves to be Trinitarian.

Tyndale is alternately cited and dismissed by a group of people known for having no qualifications in Greek, Hebrew, and Aramaic beyond knowing their way around Vine’s and Strong’s expository dictionaries.

This is especially puzzling since linguist are of one mind on the significance of Tyndale in the development of the English language. He is considered to have had greater influence on the language than anybody else, including Shakespeare. Melvin Bragg spoke eloquently of Tyndale’s influence in 2017 in St Paul’s. His genius goes unchallenged. except by his enemies.

There is a question here of understanding the value of what you are looking at. This JW apologist rightly observes Tyndale’s determination that ‘every plough boy in England’ should have and know the Bible. It is important to keep this, Tyndale’s declared intention, in focus and not assume his purpose matches yours. The full story tells of a man who bowed to neither pope, prelate, priest, or king. The story of that famous mission statement describes how:

‘A clergyman hopelessly entrenched in Roman Catholic dogma once taunted William Tyndale with the statement,“We are better to be without God’s laws than the Pope’s”. Tyndale was infuriated by such Roman Catholic heresies, and he replied,“I defy the Pope and all his laws. If God spare my life ere many years, I will cause the boy that drives the plow to know more of the scriptures than you!” (Quote copied from williamtyndale.com)

Tyndale was not on a mission to ‘prove’ the Word should have a little ‘g.’ His purpose was much different and far greater than that, and he finally paid the price with his life. However, if you don’t have the right mindset you will settle for ‘god,’ and walk away satisfied, and the poorer for it. What an education might have been yours.

History Properly Handled

The second observation concerns the handling of history. If you are going to quote or cite a sixteenth century figure it is wise to understand something of the ways of that time. This JW apologist is telling a story, recounting historical events. He tells how Tyndale worked with another Bible translator, John Rogers and how Rogers:

‘produced a bible (sic) under a different name, “Thomas Mathew” thus, “the Mathew’s Bible” came into existence and what Roger’s did was to make use of Tyndale’s NT, he did not like what Tyndale had done and that was at John 1:1, where Tyndale wrote “god” with reference to “the worde”, he changed it to read “God” in the third clause, so, instead of “the worde was god”, now, there was “the worde was God”, now we know where the KJV translators and others translations get “God” from in their NT John 1:1 third clause! Just one change of a letter changed future translations, but, such was never Tyndale’s intention, as can be seen in his work of the NT, had Roger’s not changed Tyndale’s “god” for “God”, translations might have looked a bit different at John 1:1 clause C, the third clause!’

Here our JW apologist is not only describing historical events but speaking to motive – ‘Tyndale’s intention.’ How does he know? In short, he doesn’t, he only knows what Tyndale did with John 1:1, not why he did it. As we have already observed, Tyndale translated the Bible with the express intention that, “the boy that drives the plow [will] know more of the scriptures than you!”

The apologist is confident his understanding of the work of Bible translators is correct as he concludes, ‘now we know where the KJV translators and others translations get “God” from in their NT John 1:1 third clause!’ Just one change of a letter changed future translations. Is he suggesting the translators of the KJV slavishly followed Matthew’s Bible, and all subsequent translators slavishly followed suit, because they wanted to press the case for Jesus’ deity? In other words, because their motivation was to deal a blow to Unitarianism. It seems that is exactly what he is saying.

Manuscript Sources

The Encyclopedia Britannica entry for the King James Version tells us:

‘The wealth of scholarly tools available to the translators made their final choice of rendering an exercise in originality and independent judgment. For this reason, the new version was more faithful to the original languages of the Bible and more scholarly than any of its predecessors. The impact of the original Hebrew upon the revisers was so pronounced that they seem to have made a conscious effort to imitate its rhythm and style in their translation of the Hebrew Scriptures. The literary style of the English New Testament actually turned out to be superior to that of its Greek original.’

Consider this line, ‘…the new version was more faithful to the original languages of the Bible and more scholarly than any of its predecessors.’ Ponder this for a moment. This is how translators work, from the earliest and most reliable manuscripts, the original languages, and not by simply bastardising a previous version to suit their convictions.

Britannica doesn’t stand alone in telling this story. There is an embarrassment of scholarship and commentary available to confirm these things. Scholarship, of course, doesn’t stand still and modern translators have to hand ever more, and more reliable resources than even those of the KJV translators.

A wealth of information is available, both online and in print, if you want to better understand the work of translators. Let me just point out one that is readily available to anyone who has a good study Bible. I have on my desk three Bible versions:

- The New American Standard Bible, New Open Bible Study Edition, 1990, pub. Thomas Nelson,

- The New International Version, 1985, pub. Zondervan,

- The English Standard Version, 2008, pub. Crossway.

In the preface of each I find a full explanation of the principles of translation and the textual basis for that translation. I also have access to who exactly was on the translation committee of each, something we don’t have for the New World Translation. Neither the version list, nor the scant commentary from our JW apologist give any insight, or sources, only inference and assertion. Note carefully, if you don’t know your sources you can’t know if they are reliable.

The Gospel Coalition has a helpful article 9 Things You Should Know About the ESV Bible. There is a helpful article giving insights on Bible translations in general here. Similar and exhaustive resources are available. Of course, if all you are looking for is an apparent ‘proof’ then, since you have what you want, why bother?

These are not, then, simply ‘a translation of a translation of a translation’ going back to Matthew’s Bible, as our apologist is suggesting. Why would he think this? He seems to suggest Tyndale was determined to get it ‘right’ like the New World Translation, while John Rogers was determined to drag Tyndale back to a more orthodox, Trinitarian translation, which has been followed ever since. He writes as he does to tell a story that affirms his Watchtower bias. It’s easily done, but this is apologetics not history.

Tyndale and Medieval Grammar

Why did Tyndale, in 1525, translate ‘god’ and ‘worde’ in the third clause of John 1:1? Why ‘God’ in 1534 and back to ‘god’ in 1536? It is worth remembering, I repeat, Tyndale was a Trinitarian and, whatever his intention, I believe we can safely assume it was not to take a position similar to that of the Watchtower Society of today.

It should be taken into account that what we think of as rules of grammar were not, in the medieval period, so fixed as they are today. Spelling, punctuation, pronunciation, etc. were fluid. There is a short and helpful insight available for download here. Robert Burchfield, in his seminal work The English Language, writes:

‘A period of three hundred years, in conditions of social and political stability, could presumably leave language largely unchanged. For the English language the period 1476 to 1776 is one of radical change, and it is no accident that these three centuries witnessed striking developments in social, religious, political and industrial bases of English society.’ (The Cambridge Encyclopedia of Language, p.214. OUP, 2002)

What does this look like in practical terms? Had we lived through such times how would our language have looked to us? As someone who was there, John Hart (died 1574) an English educator, grammarian, and spelling reformer… In his several works, criticised the contemporary spelling practices of his day as chaotic and illogical, and argues for a radically reformed orthography on purely phonological principles.

It was a time when, following the Norman conquest (1066), Middle English replaced Old English. We had a transition from Late Old English to Early Middle English occurring at some time during the 12th century, giving us Early Middle English (1150–1300) The growing influence of the London dialect appears from the 14th century, leading to the emergence of Early Modern English from 1540. If you wish to understand how fragmented and fast-changing the language was there is a good article here.

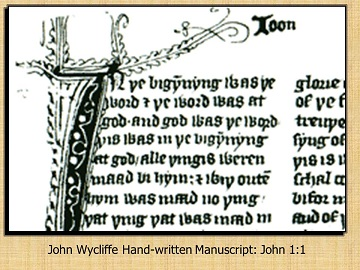

Capitalisation throughout this time was not the straightforward thing it seems today. Wycliffe’s Bible (above) almost 200 years before Tyndale reads in the original: ‘In the beginning was the word, and the word was at god, and god was the word.’

The introduction of cursive writing, and a mix of lower case (minuscule) and upper case (majuscule) coincided with a driving up of educational standards and a demand for books. The introduction of punctuation, upper and lower cases instead of the standard height lettering of the old Roman style, and spaces between words made manuscripts easier to read and write. Standardisation had begun but was not anywhere near universal until at least the 18th century.

Into this time of radical change comes the invention of the printing press with movable type (1440-1450). Writers wrote in different styles, depending on which regional style they had learned. Notably, Shakespeare spelled his name several different ways and some of his folios were capitalised while others were not. David Crystal explains:

The printing process caused complications. Many early printers were foreign (especially from Holland), and they used their own spelling norms. Also, until the 15th century, line justification was often achieved by abbreviating and contracting words, and also by adding extra letters (usually an e) to words, rather than extra space. (Cambridge Encyclopedia of Language, 1987, Cambridge University Press)

Typesetters were understandably not always sure where capitalisation fitted; to begin paragraphs? to begin paragraphs and sentences? to identify nouns, or proper nouns? ‘Inconsistent’ best describes how these things were done, from the writer to the printer.

Why did Tyndale, in 1525, translate ‘god’ and ‘worde’ in the third clause of John 1:1? Why ‘God’ in 1534 and back to ‘god’ in 1536? In light of the above, any number of reasons present themselves. Perhaps he was as unconcerned as Shakespeare would later be, writing as suited him on any given day.

Perhaps the printer made changes, depending on how he saw the work. Two things we can say with reasonable confidence; there was no fixed standard governing how he proceeded in his grammar, neither for him nor, indeed, for John Rogers and for some time to come. Tyndale was a Trinitarian and it would not occur to him that Jesus was not God, capital or lower case. The version list really tells us nothing.

Conclusion

What have we learned? Don’t take things at face value, especially when they are unsubstantiated assertions. Learn to recognise when you are being offered facts and when interpretations. It hasn’t been difficult for me to research the question of Tyndale’s various spellings, just an investment of time, some patience, a good library and a good search engine. It is easy to be overwhelmed with a little knowledge outside your own experience, but remember, ‘a little learning is a dangerous thing.’ Alexander Pope’s famous poem tells us:

A little learning is a dangerous thing;

Drink deep, or taste not the Pierian spring*:

There shallow draughts intoxicate the brain,

And drinking largely sobers us again.

*The Pierian Spring is a fountain in Pieria, sacred to the Muses and supposedly conferring inspiration or learning on anyone who drank from it. (I looked it up) Drink large, then, and grow in confidence in handling whatever ‘knowledge’ comes your way.

Resources

If you want to know more about this fascinating history you can find information on:

The journey from Old English to Modern English here

Capitalisation is discussed here

The fascinating Carolignian Minuscule here

The story of Letter Casing here

You can read about Archbishop Newcome’s text here

The New World Encyclopedia has a helpful article on Tyndale here

I can also recommend:

David Crystal’s Making Sense, The Glamorous Story of English Grammar

David Crystal’s Cambridge Encyclopedia of the English Language (Honestly, anything by David Crystal is a treasure)

Robert Burchfield’s The English Language

Doug Harris’ Awake to the Watchtower